This is a chapter from my bachelor’s thesis at Anglo-American University’s School of Journalism (2019). Read the full version here: Long-form article on Vietnamese Immigrants in the Czech Republic.

The List of Names

“Ha…T..h..an..h.…,” the teacher squinted her eyes to look at the letters, struggling to pronounce her new student’s name. Eventually, giving up, Ha Thanh’s kindergarten teacher gave her a new name for convenience: “Hasika.” The name “Hasika” does not have any meaning, while “Ha Thanh” means “green river” in Vietnamese.

“At that time, I didn’t speak any Czech,” said Ha Thanh Špetlíková, now an actress and entrepreneur, in an interview with Lidovky in 2010. “I saw that the teacher wrote “Hasika” next to my name. I didn’t understand what it meant. In primary school, Hasiku sounds like Jessicu so I answer to both names.”

Having a name in the local language is the first step for any immigrant to integrate into the society of the host country, especially when it helps him/her find jobs or places to stay.

A research by Center for Economic Research and Graduate Education shows that Vietnamese immigrants must apply for twice as many apartment advertisements as Czech people in order to be invited for a view. Czech job seekers are also 180 percent more likely than Asian immigrants to earn an interview when applying for jobs.

A similar experiment done in the United States in 2016 shows that second-generation Irish, German and Polish immigrants with “very ethnic names” earn $50 to $100 less per year than those with “very American names.”

“If you want your child to be more sociable, confident and able to avoid unnecessary troubles, you can choose a Western name for him or her,” says Vuong Thuy-An a Vietnamese mother of two living in Prague, President of the non-profit Lam Cha Me CZ (Parenting in the CR).

On Easter 2019, Thuy-An organized a trip for several Vietnamese mothers and their children to Budapest. Coming along with the group is a Chinese boy whose name hardly anyone could pronounce or remember.

“People mispronounced [the boy’s] name into funny sounds,” An says. “He didn’t enjoy it and was unhappy whenever his name is called. Sometimes he sighed in reaction to hearing it, but never dared saying anything. Every time this happened, I only wished his parents had given him a Western name to make it easier for others to call him.”

Thuy-An herself knows the struggle of naming children in a multicultural environment. Her husband is Chinese. Their nine-year-old son Filip has a beautiful Chinese name 吴蒙捷 (Wu Mengjie), given to him by his grandfather, which means health and strength. Only one problem: the middle name 蒙 (Meng) is translated into “buttocks” (Mông) in Vietnamese. Thuy-An, therefore, for convenience, gave her son a Czech name “Filip,” a name Czech, Vietnamese and Chinese people can all pronounce.

Multiple Identities

Psychologist Erik Erikson, known for his theory of identity crisis, says people develop their sense of “self” around the age of puberty. During this period, we ask ourselves questions such as “who am I,” “what is my purpose,” “who do I want to become,” and so on. For children of immigrants, this is extra challenging because they are under the influence of two or more cultures. Sometimes, in order to cope with the identity crisis, they deny one of the two identities.

“I’m more Dužan than Duc,” says the Vietnamese-Czech movie director Dužan Duong (Vietnamese name: Duong Viet Duc) in an interview with Czech Radio in 2016. “But at home, when I’m with my parents, I’m still Duc. And I will always be Duc at home.”

Dužan doesn’t speak Vietnamese. In 2014, he made a short docu-fiction film named “Mat Goc” (Rootless) based on his personal experience with identity crisis.

The movie features him and his brother visiting Vietnam for the first time, overwhelmed by the culture shock.

Bullying and Discrimination

While the Vietnamese culture shocked Dužan, the Czech culture shocked Thu Vu when she first set foot in the CR at the age of six. Hiding behind her big leather purse, Thu sobs as she recalls her early experiences in the Czech Republic. It’s been years, but the painful memories still haunt her.

“At the time, I couldn’t get used to my new life in the Czech Republic,” Thu says. “Meanwhile, my friends in Vietnam had already forgotten me. I didn’t know who I was, or where I belonged.”

When Thu went to school, her classmates mocked her for her Asian appearance and accent. After the initial struggle with the language, she slowly became fluent in Czech, and her academic performance spiked. But that only made her situation worse. Thu became a subject of envy. “Some girls provoked me to fight them after school,” she says. “They spread terrible rumors about me. The situation got out of hand, and the police arrived at school to question me. I didn’t want to go to school anymore.”

Thu was not the only Vietnamese student to suffer from bullying. In the research done by Alex Tran on 120 second-generation Vietnamese, 58 percent of the participants have reportedly experienced racist and/or xenophobic assaults during their time in the CR, 86 percent of which were verbal. These attacks harm their self-esteem and pride, make them question their identity and sometimes, leave deep scars in their hearts.

Ondra Nguyen was another victim of bullying. After two older students beat him up for no apparent reason, his sister came to talk to the teacher. Ondra did not want people to know about the incident, but the injuries were hard to hide. He was ashamed.

“I used to hate being Vietnamese.” says Ondra, now a student at University of Economics in Prague. “When I was young, maybe 12. Something like that. It’s very difficult being Vietnamese in the Czech Republic during those times. I think it wasn’t just my problem, but of many Vietnamese. I heard it from some Vietnamese they hated being Vietnamese in the CR when they were younger.”

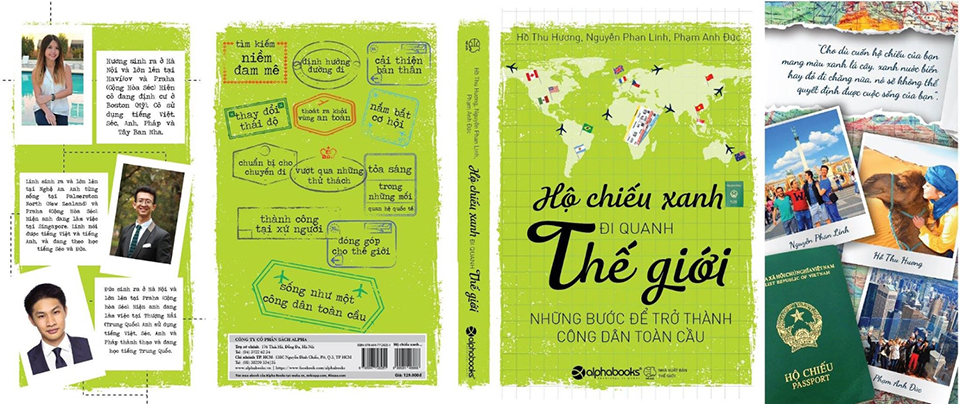

In her book “Green Passport Goes Around the World,” (Hộ Chiếu Xanh Đi Quanh Thế Giới), Ho Thu Huong describes in detail how she was verbally and physically assaulted by Czech people during her teenage years in the small city of Havířov.

One time in primary school, Huong and her classmate Veronika went for a walk and passed a playground where four boys, the same age as them, were playing. Veronika knew the boys, so she dropped by to say hi. But before she started her greetings, Huong already heard what she had expected. “I heard ‘China! China!’” Huong writes in her book. “I wanted to walk as fast as I could from those children. But they wouldn’t let us be. They followed us like a tail. As we sat on a swing, the smallest boy hit me in the head with a long stick. Other boys threw rocks at me. I ran home, slammed the door and cried.”

Growing Pain

Huong did not let the racist slurs or violent attacks bring her down. She turned them into motivation instead. “It is always a big challenge to be an immigrant,” Huong writes. “Until the world tears down all prejudice, immigrants everywhere have to fight for themselves.”

Since then, she studied hard to prove her abilities, won numerous academic competitions and gained opportunities to travel abroad for study and work. Now 31, Huong has traveled to 25 countries and is fluent in five languages. In 2016, she co-authored with two other Vietnamese to write “Green Passport Goes Around the World” and told their stories of living, working and traveling around the world.

The book made it to the top 20 most valuable books in Vietnam in the same year. The labels people put on Huong no longer bother her, she says in her book, because she knows who she is. She is a global citizen. She does not belong to a single nation but the world.

Ondra also found a way to fight for himself and regain confidence. After the assault, he started learning martial arts. A few years later, on his way out of the supermarket Kaufland, Ondra heard a drunkard said something racist about him. “I waited outside for the man to finish his shopping, and then I just beat him up,” Ondra says. “I was stupid. I was young. I wanted to show off to people that I’m Vietnamese but I’m confident.”

Fortunately, Ondra does not fight on the streets anymore. Now he practices boxing and dancing with a personal trainer. “I work out because it’s a lifestyle,” Ondra says. “I’m glad the two guys beat me up that day. That’s how it all started. Everything. My behaviors. My attitudes to life. Who I am today. I’m very proud of it.”

Social Labels

No one can avoid being labeled. In his book about stereotypes and prejudice, Charles Stangor, professor of psychology at the University of Maryland, asserts that since prehistoric times, for our own safety and livelihood, humans have learned to judge quickly and put people in boxes of friends and enemies.

But social categorization and stereotyping have pros and cons. Social boxes exaggerate the similarities among people in the same social group as well as the differences between social groups. Insults and violence between social groups often deepen the divide and contribute to the stereotypes. Derogatory labels affect people’ sense of identity.

As we have seen, second-generation Vietnamese have various ways to deal with their labels. Some deny the labels. Some reclaim. Others turn them into fuel for success. No one can avoid being labeled, but everyone can choose how to deal with it.

Leave a Reply